I recently caught up with Andrew to chat about what he’s learned becoming a design manager. Andrew is currently Director of Design at Grand Rounds. His career has spanned from research institutions, to design agencies, to small startups, and large companies. He loves working on multi-sided marketplaces and has a deep fondness for internal tools. But his true passion is helping his teams be awesome at what they do.

How did you find your way to being a design manager?

After working at Vivid Studios, I joined eBay as a designer, which was about 9 months after they went public. I was there for five and a half years, and that’s when I grew from designer, to senior, to lead, and then made the jump over to manager. I moved into the manager role because I was more engaged with helping people and teams be successful, than doing the work myself. I enjoyed figuring out how to unlock people’s potential.

As a new manager, I arrogantly thought that I knew it all. When Salesforce called looking for their first full-time design manager, I said, “Sure, I can do that!” I went there, and I very clearly couldn’t.

Almost all new managers are somewhere between okay and awful. I was nudging closer to the lower third of that spectrum. I made a lot of the mistakes.

What was your biggest mistake as a new manager?

In hindsight, the mistake I made was managing other people the way I like to be managed, rather than the way they wanted to be managed. One of the things I came to understand was a model called Situational Leadership. It’s basically the notion that there’s a relatively predictable evolution for any given skill.

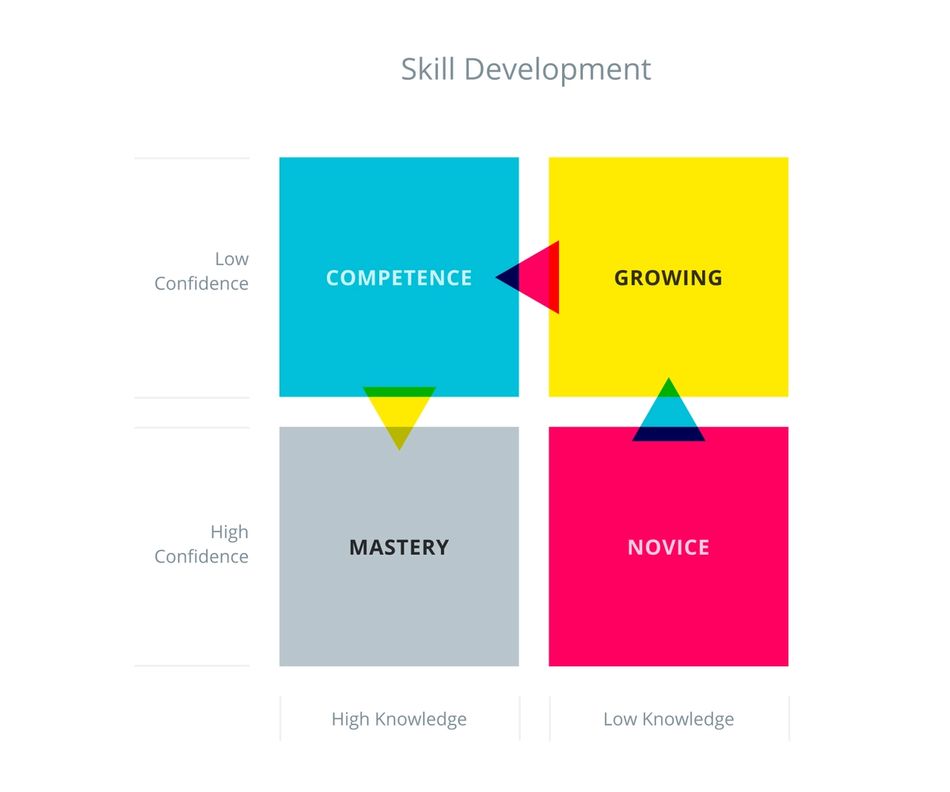

You can think about it as a 2x2 matrix.

When developing a skill, we all start as a novice where we’re incredibly excited and committed, but have very little knowledge. As we gain experience and understand the scope of a problem, we become fearful of failure because the full scale of thing that we’re tackling becomes apparent.

As we move through that fear and into to competence, our commitment and emotions still vary, but we know what we’re doing. Finally, we attain mastery. We know what needs to be done, how to do it, and we’re confident.

How you manage somebody in each of those phases differs.

How do you manage differently when people are in each of those phases of skill development?

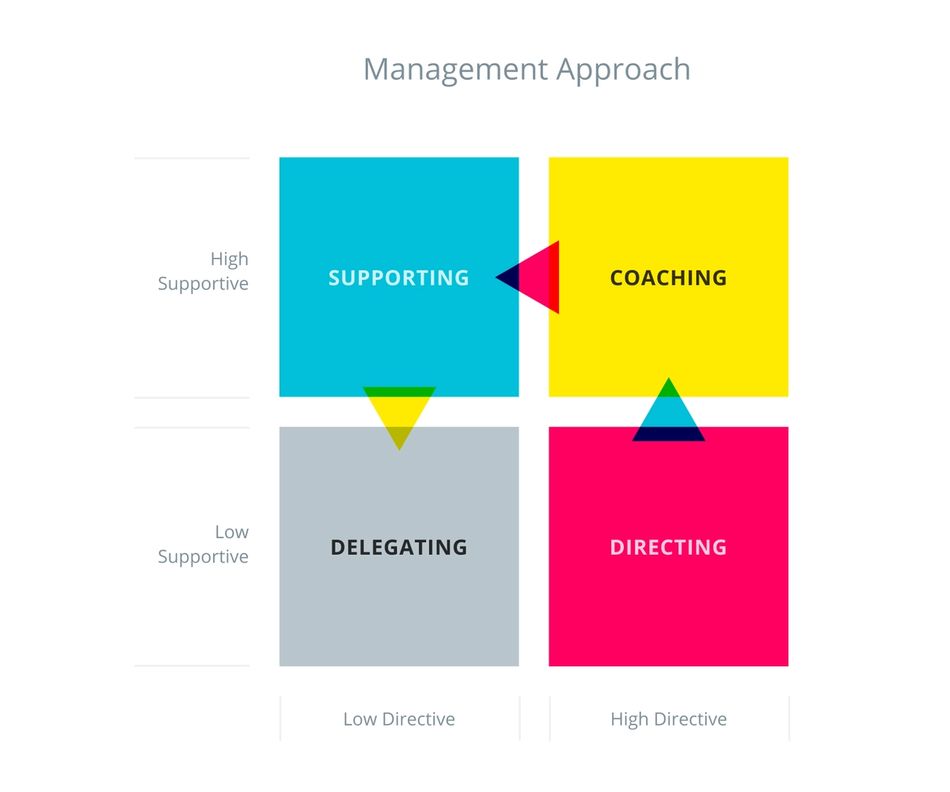

When people are in the first, really excited phase, you want to be relatively prescriptive.

“I’m glad you’re excited, I’m excited to work with you. Here are the 3 things I need you to do.”

When people get to the “oh my god” point. Say, “I’m with you, we’re in this together. Here’s what I suggest you do. What do you think?” As a manager, you’re going from prescriptive to coaching.

Once people make it to the competence point, then it’s more supporting. Say, “I understand you’re feeling this way. Here’s the problem we’re trying to solve. What would you do? How can I help?”

And when people gain mastery, management becomes more about delegating. “Here’s the problem I need solved.” You give as much support as they need, but this is where people are relatively autonomous. I find that master craftspeople tend to think “What’s the problem? What’s the desired outcome? Great. I got this.”

Now that you understand situational leadership, why do you think you were struggling in your first management role?

My biggest mistake was being prescriptive with my senior designers (because I wanted to make my mark) and being very permissive with my junior designers (because I wanted them to explore the way that I like to explore). That was probably the antithesis of what I should have been doing.

I was working with incredibly thoughtful and strong designers. But I thought I knew where I wanted to take the product and the team. Rather than managing through influence, I tried to manage through positional authority: “I need you do go do this.” I wanted the product to be a reflection of my aesthetic and my desire rather than the user need. I learned that it’s awful to do that.

My crucial mistake was to say, “Make it this way because I want it this way.” By using position rather than influence, in the end, you lose the trust of the team you’re trying to lead.

So you’ve moved away from thinking about your design teams as a means to build your personal vision. How do you describe the purpose of your design team now?

We are at our best when we clearly understand the user need, articulate it in a way that makes sense to everyone, help people empathise, and bring them along with storytelling. That’s true for designers, leadership, everyone.

As a design team I think we’ve got three superpowers within an organization.

The first one is we need to be a strong voice for the user throughout the product development process. We rarely own the relationships with customers. You might have frontline sales or account management or customer service that is really there with people. But design needs to understand customer needs, be able to articulate those, and carry them through the entire process. When the broader project teams start making trade-offs, we need to raise our hand and say, “Is this in the best interest of the user as well as the company?”

The second is that we need to be strong partners to product and engineering. To get a seat at the table, we need to have a sense of what both teams do and what they’re accountable for. We don’t need to be coders, but we have to understand how the code gets written, built, and deployed. We don’t need MBAs, but we have to understand the business model, or it’s hard to be taken seriously.

The third thing we do, and it’s truly our superpower, is we’re creators of possibility.

We are the whiteboard for the organization. We help make things that never existed become possibilities.

Our superpower is to prototype, to ideate, to instantiate things that have never been. And in doing that, you can often set a direction, and a vision, and a guiding north star. If that aligns with the organization’s principles, you can unlock an incredible amount of value for a company.

Designers love north star projects, maybe a little too much. I agree these projects need to align with the organization’s goals in order to be successful. How do you make sure that happens?

The vision work is the piece that we generally feel great about because it goes on Dribbble and it goes in our portfolio. It’s raw, active creation.

But the day to day trade-offs, those are the hard conversations. You design this amazing product, and then engineering comes back saying, “Great, but we can only get a third of it done this quarter.”

Then you’re faced with some hard questions: Do we build it or not? Am I violating my design conscience by not building the whole thing? Is it going to be a useful and usable product when it’s stripped down to the thing we can build? That’s the hard work. That’s where the actual sausage is getting made.

If you’re going to be a craftsperson, you have to be able to execute at every level of the craft. It’s not enough just to draw the blueprints, you’ve gotta build the house. You have to make painful trade-offs around what can get built, and then figure out the next steps, and stick with it. You have to have grit.

The analogy I like is builders versus gardeners. It’s not just about presenting a design. It’s about constant tending, care, and maintenance to get your design to thrive. It’s not dropping the seeds and walking away. It’s not throwing some water on it once in a while. It’s constant attention to making the design better and making the environment better.

How do you encourage this practice of gardening?

For everybody on my team that’s a senior and higher, I ask them to be willing to sign up for a 9–18 month commitment to a particular product area with a known set of product and engineering partners. And that’s for two reasons. The first one is, it takes a while to get your head around a space. Understanding a problem at depth requires a certain amount of investment, digging in, and immersing yourself. The second one is that relationships are built on trust, and trust takes time.

Do you do anything to encourage these relationships? Or do they just happen?

For my team of designers, when they demo work to the design team, their product partner is sitting in the room with them. We ask designers to frame their work. What’s the problem we’re trying to solve? What does success look like? What’s our time frame? What type of feedback are you asking for?

So there’s no mystery. If design and product are not communicating, it becomes very clear that there’s a gap. If the PM can’t stand up and say, “This is the goal, this is why, this is how, this is where we are,” then we have an issue.

When PMs are at the design review, designers are more anchored into why this project matters and the expectations for it.

Okay, last question: What books that have changed your mind about leadership and design?

One of our investors at Grand Rounds is Harrison Metal, which is led by Michael Dearing, who was GM at eBay while I was there. I was lucky to be able to attend his general management course. So for the very first time, I read High Output Management by Andy Grove. It’s an intriguing model.

The other book that’s really interesting is Orbiting the Giant Hairball. It’s about a long time creative at Hallmark and how he created space for the design team to think about things differently. It’s great.

And then the last book, without sounding trite, is How to Win Friends and Influence People, by Dale Carnegie. Because at the end of it, work is really about people and building trust and credibility. Everything we do, unless you’re a sole practitioner, is dependent on other people to do well.

Andrew Sandler is Director of Design at Grand Rounds, whose mission is to create a path to great health and health care for everyone. Learn more about design careers at Grand Rounds.